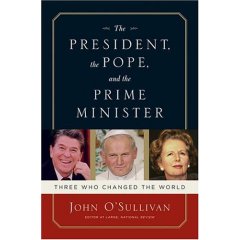

John O'Sullivan, editor-at-large of National Review, has brought the intersection of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the Vatican, and 10 Downing Street to life in this history of how the leadership of Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul II and Margaret Thatcher accelerated the decline of the Soviet empire and combined to throw socialism on the "ash heap of history".

The author begins by demonstrating how each of these three individuals were thought of to be steady yet unspectacular foot soldiers in their various causes, which led to the underestimation of each of their to lead, inspire and affect change when they reached higher office. In the case of Reagan, stagflation and the national humilations of Watergate, Vietnam and the Iran hostage crisis allowed a sunny optimist to thrash the sincere yet impotent Jimmy Carter, who was facing a threat from Ted Kennedy in the 1980 primaries. Thatcher, a former Education Minister and unabashed free-marketeer who believed in a vigorous foreign policy, defeated the interventionist Red Tory Edward Heath in the mid-1970s and forced the Conservative party in England to live up to its name. And finally, John Paul II, the first non-Italian Pope, was a traditional yet bridge-building intellectual cleric from Poland who refused to accede to the lure of hard-left, almost overtly Marxist liberation theology.

O'Sullivan's book leaves one with the impression that the starting point for how each of these three undermined the Soviets began with John Paul, who insisted on preaching about freedom of religious expression in his native Poland at the turn of the decade between 1979 and 1980. As the totalitarian, socialist state crushed religious liberty and saw the citizenry as subjects in its service rather than free and dignified men and women, John Paul urged Poles to think of themselves not as a Communist country but as a Catholic one. This soon led to the emergence of Solidarity, a democratic labour movement which demanded rights for workers against the powers of Warsaw, Moscow's client, who would allow little quarter. However, in relatively short order, the power of the Catholic Solidarity movement was too strong for the state to resist and so liberal democratic freedoms for both practicing Catholics and trade unions were soon allowed as argued for by the Pope, eventually fostering a belief in the possibilities of independence for even the most average of Poles.

In the case of Thatcher, upon taking office, her reforms to the bloated, lumbering British government were brought in with rapidity which endeared her to free market conservatives in Washington and elsewhere. At the sake time, she re-established England as both a cornerstone of NATO and as a reliable ally of the US - economically, at the G-7, and on foreign policy, when it came to resisting Soviet expansionism in Latin America, Africa and elsewhere.

And Reagan. His Westminster address, the reference to the Soviet Union as the "Evil Empire", and his challenge to Mikhael Gorbachev, a man whose historical role was essentially one of re-arranging deck chairs on the Titanic, to "tear down this wall" flew in the face of conventional wisdom. The President's assertive belief in the ability of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) as an alternative to the conventional arms race was a principle he maintained all throughout his time in office, and as O'Sullivan states, he even offered to share the technology with the Russians, who at one point were spending well north of 25% of their gross national product on defense just to keep up. Gorbachev miscalculated and said no.

Pivotal to all this was the Reykjavik summit of October 1986 where the Russians tried to get Reagan to eliminate all nuclear weapons within ten years and also to stand down on SDI. For O'Sullivan, Reagan said no, despite being tempted, because he believed that the Star Wars program as it was otherwise known would allow for a halt to conventional weapons development since it would provide a deterrent against Soviet aggression like nothing ever seen before. In December 1987, Gorbachev finally capitulated, signalling something that could have ended 15 years prior had someone like Reagan been in office and willing to see it through at the time: the Soviets could not compete. On a tour of Moscow in May 1988, he was mobbed by ordinary Russians and later that year saw Gorbachev unilaterally reduce Russian forces by 500,000, its tank division by 25%, and combat aircraft by 500.

By the time Reagan left office, the dominoes in Eastern Europe had begun to fall, beginning with Poland and then spreading all throughout the Iron Curtain. Gorbachev, a socialist at heart who was viciously mugged by reality, saw the Wall crumble in November 1989. In fact, as he tried to save himself in the years after the Iron Curtain fell, he even referred to John Paul as "the highest moral authority on earth" in a feeble attempt to garner the Pope's support for his post-Communist vision of state planning, but no matter as in May 1991, the annual May Day parade in Moscow was cancelled and Gorbachev's rival Boris Yeltsin soon consolidated his hold on the post-Soviet Kremlin.

At times, O'Sullivan is a tad too theological for my tastes (and I would venture to guess that I am more familiar with the dictums of Catholicism than most). Moreover, he implies that since all three were able to survive attempts on their lives, there must have been some bigger purpose guiding the world in the 1980s. A little hokey, that, but O'Sullivan skillfully resists the temptation to descend into jingoism. His recounting of the many armed conflicts throughout the decade such as Grenada and the machinations around the Iran-Contra affair are also very clear (even if he does overstate the importance of the Falkland Islands conflict in Thatcher's prime ministership). As for behind the scenes impressions? The aforementioned American left-wing icon Ted Kennedy approached the Soviets in Reagan's first term to strategize with them as to how to outwit the President, and Gorbachev is portrayed as a well-intentioned yet proud and nationalistic man who found himself in challenging, inevitable circumstances.

All told, the determined leadership of Reagan, Thatcher and Pope John Paul II set in motion a turn of events that re-united Europe and marked, at that time, the "end of history". We know now that even though that history is written by the victors, there are many who would discount these three remarkable individuals and so it is vital that books like "The President, the Pope and the Prime Minister" receive their just due as elites in the West are quick to distance themselves from the possibilities offered by spirituality, steely resolve and a proud belief in the system of free-market, liberal democracy as the best structure by which to organize human societies.

Overall rating: 8.5/10